Essay by Andrea Vitali, 2019

On the occasion of the publishing art Lo Scarabeo di Torino's facsimile edition of the Sola Busca Tarot, the following represents the text accompanying the deck, prepared by the writer and published in six languages together with the deck.

Translation from the Italian by Michael S. Howard, February 2019

This precious Tarot deck previously belonging to the Marchessa Busca, born duchess of the Serbelloni family and married into the Busca family, was acquired by the Italian Ministry for Cultural Resources and Activities in 2009 and assigned to the Brera Gallery (Milan). It is a deck of 78 cards measuring 144mm x 78mm, illustrated in the antique style. The cards were lightly engraved in copper, as strokes of the burin can be clearly seen through the superimposed colour, where traces of the lines are clearly visible.

Leopoldo Cicognara in his work of 1831 Memoria spettanti alla storia della calcografia (Memoir to serve the history of intaglio printmaking) wrote that Abbot Zani had told him he had seen the same edition divided into two “Gabinetti” in Naples. This information proved correct, as was eventually verified by Cicognara, who confirmed the same numbers, dimensions and quality of work. Currently other examples are known - not illuminated - in the collections of the Kunsthalle in Hamburg (4 cards), the Petit Palais in Paris (4 cards), and the Albertina in Vienna (23 cards).

The presence of cards belonging to the same deck but not coloured has suggested that the deck in Milan after being engraved was then painted by a Venetian artist with the addition of various inscriptions. The result is a deck where the number of cards, divided into Triumphs, number cards and courts, is identical to the known standard structure of today, which is 22 Triumph cards (Major Arcana) and 56 number and court cards (Minor Arcana). The year of the pictorial intervention has been deduced from the text that appears on Triumph XIV (Bocho): permesso del Senato Veneto written in the year ab urbe condita MLXX (1070), which should correspond to 1491, given that the Venetian era ad urbe condita begins in the year 421 of the common era and not from 453 as was believed in the past.

There is a great difference between the Triumphs of this deck and the canonical figures, in that - apart from the Mato [Fool] which was drawn according to a generally common iconography of the time - the remaining Triumphs represent famous personalities from ancient Rome and biblical times (along with others that are not easily identifiable). This follows a baclward-looking tendency, as can be seen from the cycles of “Famous Men” in the 14th century, of exempla to imitate. Among the ancient Romans there is Mario, probably Caius Marius, Trump IIII; Deo Tavro, Deiotarus, VII; Nerone, i.e. Nero, VIII; Catone, Cato the Younger, XIII; and Bocho, in all probability Bocchus, king of Mauritania, XIII. Among the historical personalities described in the Bible, Nenbroto, XX can be recognized as Nembroto, an alternative name for Nimrod, and Nabvchodenasor, who is Nebuchadnezzar, XXI. Meanwhile the others, according to the art historians at the Brera Gallery (where an exhibition was held of this deck in 2013), have uncertain identities, including Postvmio, II; Catvlo, V; Sesto, VI; Tvlio, XI; Carbone, XII; Metelo, XV; Lentvlo, XVIII; Sabino, XVIIII; Panfilo, I; Lenpio, III; Falco, VIIII; Ventvrio, X; Olivo, XVI and Ipeo, XVII. For these historians, as they wrote in the exhibition catalogue, every attempt to reach a correct identification remains destined to fail “until a full analysis of the classical sources and the medieval compendiums available from the 1400's is undertaken in relation to the individual personages” (1).

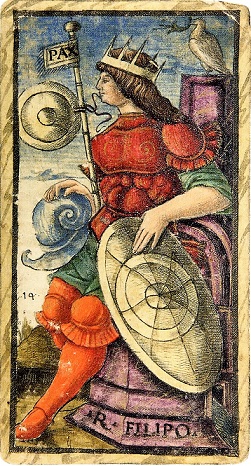

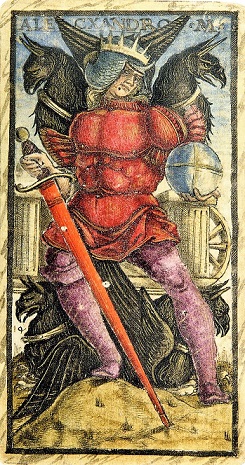

Regarding the court cards, the role of the King of Swords is assigned to Alexander the Great, while in other cards various famous persons can be found, such as King (Rex) Phillip, the father of Alexander, on the card of the King of Coins; Helen of Troy as the Queen of Coins and Olympia, mother of Alexandria, as the Queen of Swords. The court cards are based on medieval romances that drew parallels between figures of the Trojan War and others from the life of Alexander the Great.

King of Coins King of Swords

Queen of Coins Queen of Swords

The iconography of the number cards has left room for various interpretations. One of these is proposed by the scholars of the Brera and is based in part on the descriptions ofalchemical procedures. However other experts have hypothesized a different interpretation, explaining them as an expression of moral Christian teachings. With a view to parity, both versions are reported here.

The inclusion of these cards within a description of an alchemical process can be justified from the existence in Italy of important manuscripts in which fourteen texts are gathered that are attributed to Hermes Trismegistus, the mythical inventor of alchemy.

The belief in this Hermes is considered today to be without any real basis, given the proven non-existence of that individual, who was probably identified with the god Hermes, otherwise known as Mercury. In any case, the Middle Ages and the Renaissance believed in his real existence, which is why it would seem logical that this belief was somehow reflected in a Tarot deck.

As alchemy aims towards the creation of gold through the purification of base metals the philosophical speculations that this practice implies are of great interest: the purification of the soul via the liberation of earthly desires, as symbolized by the base metals. Furthermore, as the structure of the Tarot in the 22 Triumphs expresses, as we know today, the Christian Mystical Staircase, yet another way of teaching man the awareness of his own divinity according to another reading of the cards. in this case alchemical, these interpretations appear more than acceptable.

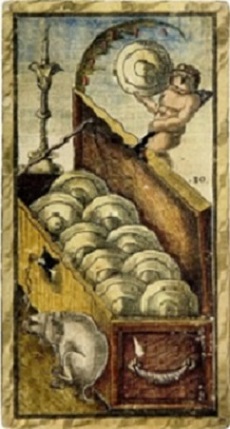

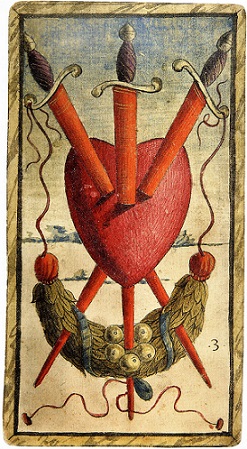

Alchemy also extends to the pursuit of the lapis philosophorum [philosopher’s stone]andthe elixir, via the process of transforming matter, beginning from gold and silver. Besides being a state of perfection, it would have proved to be the medicine capable of guaranteeing a long life. This is mirrored in that yearning for immortality felt by Alexander the Great and attributed to all the individuals described in the Triumphs and court cards. Following on from this conjecture, the Brera scholars saw in the cards of Coins a collection of silver florins - from their transport (the Three of Coins) up to their hoarding (the Ten of Coins). In the Cups, and specifically the Ten, is the image of Hermes Trismegistus. The turban on his head is connected to a watercolour effigy of him present in the book Secreta Secretorum philosophorum datable to 1470. The Baton cards would be a reference to the relationship between the opus alchemicum and agriculture. For example, the Three, illustrated with a head pierced with three Batons, expresses the necessity for secrecy in transmitting alchemical knowledge. This is also symbolised with the person’s mouth being closed by a garland, and with the two eagle wings placed on either side of his head - symbols of the Mercury of the Philosophers. Taking the Three again as reference, this time of Swords, the heart that is its representative is proposed as a symbol of fire, a vital component of alchemical procedures, while the Three of Swords expresses again the three metals described in reference to the Three of Batons.

Three of Coins Ten of Coins

Ten of Cups Three of Batons

Three of Swords

The Brera scholars have identified Nicola di Maestro Antonio, of the Marches region of Italy, as the person who created the deck. He was trained in Padua in the style of Squarcione and is documented from 1465 until 1511. But the idea of the project should be attributed to Lodovico Lazzarelli, a humanist born in 1447 in San Severino, also in the Marches. He was very close to the hermetic culture of that time. Other than the inscription MS added to the aces and other cards, the same scholars believe that the possible commissioning of the extra work done could be ascribed to a Venetian man of letters Marino Sanudo the Younger (1446-1536).

Other authorities nonetheless disagree with what has been hypothesized by Laura Gnaccolini, curator of the exhibition and of the Brera catalogue, and by Sofia di Vincenzo, to whom she makes occasional reference. For Michael S. Howard, former philosophy professor at the State University of New York in Albany, Gnaccolini's alchemical vision obscures other ways in which the cards can probably be interpreted. The face of a bearded man with a hat, perhaps a turban, surrounded by ten Cups does not necessarily mean it is Trismegistus. The Sephardic Jewish moneylenders and merchants, who were numerous in Northern Italy during that period, also had a similar appearance. The fact that his face shows a certain diffidence suggests, if indeed he is surrounded by riches, that he is thinking of the danger of losing these riches at any moment. As for the number three cards, this number is more commonly associated with the Holy Trinity. For example, the three Batons that go through the head of a child in that same card, have nothing in common with the alchemical illustrations of metals but rather suggest the nails that were driven into the flesh of Christ in the three upper parts of the cross. The wings and the garland of victory meanwhile express the child’s future ascension. As for secrets, the alchemists did not denote them with a metallic pin in the mouth but with a finger on the lips. The pivot could be there simply to support the garland. In any case the Christ child did have a secret, that of the choice of his death. Venetian art at the time often showed the Christ child held by a sad Madonna, as if she already knew the destiny of her son.

But a Christian orientation, continues Prof. Howard, is best demonstrated in the Three of Swords. As the alchemical illustrations do not show flames or other items that corroborate the indications of the Brera scholars that the Three swords as they are positioned could represent gold, silver and mercury exposed to the flames of an alchemical process, it is therefore necessary to consider the contrary, that the image of rays that pierce the heart of the believer was quite usual in Italian art between the end of the 14th and the first half of the 15th centuries. A point of reference can be found in a passage from the Confessions of St. Augustine, Book IX: “You have pierced our heart with the arrows of your love” (Saggitaveras tu cor nosrtum caritate). Some painters depicted Augustine showing his heart pierced by rays emanating from a vision of the crucifixion. Filippo Lippi (1437-1438, Florence), painted him with his chest pierced by three rays emanating from a vision of the Trinity. It therefore seems more probable that the cards make reference to this tradition. (2)

If this scene could invite an alchemical interpretation, affirms Howard, a theological derivation also exists. What impact do the three components of the Trinity express on the human heart? The severity of the Father is mediated by the Holy Spirit that descends on Jesus at the moment of his baptism, determining the redemption of humanity through the sacrifice of his Son. This progression could be considered with the nigredo as the blackness of sin, the albedo the whiteness of the dove and the rubedo as the red of Christ’s blood. Each stage pierces the heart in its own way, finalized in salvation, represented by the garland. We can therefore hypothesize a Christian interpretation that uses alchemical images - so-called “spiritual alchemy”- rather than a simple description of the transformation of metallic materials. A Christian vision that can also be found in the other suit cards of the same number.

The Sola family gave photographs of the deck to the British Museum in 1907. The cards realized by Pamela Smith for the deck created by A.E. Waite took inspiration from some of these, including the one of the heart pierced by three swords. Waite, however replaced the garland with a rain cloud, in this way modifying a scene of suffering ending in joy into another of only sadness.

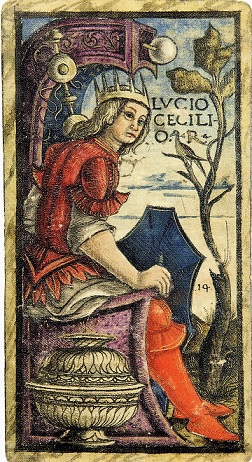

According to the mathematician and Tarot historian Mauro Chiappini, the various inscriptions present on some cards could be correctly interpreted as anagrams. Chiappini asked himself: “Various inscriptions present evident spelling errors, such as the Queen of Cups, Polisena instead of Polissena; the Queen of Swords, Olinpia instead of Olimpia; the Knight of Coins, Sarafino instead of Serafino. Who is this Knight Sarafino? Who are the King of Batons Levio Plauto R. (Rex) and the King of Cups. Lucio Cecilio R., absent from the history of Rome both in title (there were only 7 Kings of Rome, beginning with Romulus), and in name. In the Triumphs, who are Lenpio, Venturio, Olivo and Ipeo, of whom no trace exists in Roman history, placed alongside Cato and Nero?

To understand this, for Chiappini the most reasonable explanation is that here we are confronted with an “intentional error, placed deliberately to make us discover something else”, names deliberately utilized to hide another meaning. In other words, a linguistic expedient that should lead to another, as if the inventor enjoyed himself by placing within the deck a game within a game. In those times, among techniques of this kind - other than the Notarikon, i.e. the acrostic, or the Gematria of Jewish origin that assigned a numerical value to each word - the anagram was used. Francois Rabelais, who signed himself “Alcofribas Nasier”, and Pietro Aretino, “Partenio Etiro”, are just two among many examples that could be cited.

Resolving anagrams of names present in the court cards actually provides a surprising result. For example the cards of Cups, considering the Knight Natanabo, the Queen Polisena, and the King Lucio Cecilio R. and proceeding with the anagram, results in “l'ocio lucica pianto a l'insano bere”- a phrase that translates to advice on using drink with the same moderation that should be used in all aspects of life, thus becoming whatever moral sentence relates to that suit. Applying the same procedure to Swords, Batons and Coins, Chiappini attained coherent phrases, responding again to moral values.

Knight of Cups Queen of Cups

King of Cups

Fundamental to understanding a different designer for the deck than the one attested by the curators of the Brera, are the phrases that are found on the Ace of Coins: “Servir chi persevera infin otiene” (He who perseveres reaches his goal), which borders the shield supported by an angel with raised arms, and Trahor Fatis (I yield to Fate) put on a scroll supported by another small angel, below on the left. By making anagrams of the two phrases, the result is: “Ho trist' a far per servire Rino Fieschi Venetian” (I did this work for Rino Fieschi Venetian).

Ace of Coins

The anonymous Venetian painter who added the inscriptions to the original deck, besides lamenting the work he was commisioned to do - it was more an artisanial job than an artistic one - indicates here the name of his employer: It is Rino (a diminutive of Ettore) Fieschi, from the noble Genoese Fieschi family. The grandfather, his namesake, was the same Ettore Fieschi who tried to pacify the parties in the famous conspiracy of 1547 promoted by Gianluigi Fieschi against Andrea Doria and the Genoese Republic. The fact that the Fieschi family attached themselves to the Venetian nobility is nothing exceptional. Other Genoese families had done the same in the past, amongst those the Cibo family, and had obtained the same benefits.

Among the many Ettore Fieschis present in the genealogical tree of this Genoese line, the Rino in question here had taken a wife of the Genoese nobility, a certain Tommasina Spinola, known as Masina Spinola. On the Aces of Swords, Batons and Cups, appear the two capital letters M and S. These are the initials of his wife that her husband wished engraved on the cards, like the trademark of a family business. This is further enhanced by the colours used on the coat of arms that can be found on the shield of Bocho and also present on the Ace of Swords and on the shield of Mario. The coat of arms of the Spinola family is in gold with central squares in red and silver, the same colours that can be found on the cards with the variation of the crosswise sash that belongs to the Fieschi coat of arms.

The historian Chiappini does not believe therefore that the initials M.S. refer to the Venetian man of letters Marin Sanudo the Younger (1466-1535) nor to the Ferrarese miniaturist at the end of the 1400s, Mattia Serrati da Casandola, as the iconographer Hind presumably had assumed. The marriage between Rino Fieschi and Masina Spinola ocurred in 1584. The cards therefore were produced from that date onwards, not prior, otherwise there would be no logic in using the two initials of Masina Spinola. Nevertheless, in order to determine the probable date of their production there appears the fateful inscription on the shield of Bocho (XVI): Anno ab Urbe codita MLXX. Making an anagram of the phrase in question we get: “XX abbiam de l'anno Turco”. The year of the Turk referenced here is the celebrated Battle of Lepanto in 1571, when on the 7th of October the Holy League composed of the Genoese, Venetians and Spaniards, defeated the Turkish armada at Lepanto.

Having determined that 1591 was the most likely date when the anonymous Venetian artist contributes his variations on commission of the Genoese noble Rino Fieschi, Chiappini attempted to identify the possible commissioner and executor of the original deck. The only help in this instance was from the inscriptions present on the Triumphs, and there were only two:

- S.C., written on the chariot of the Triumph Deo Tauro (VII) and on the small flag at the top of the pole of the Triumph Metelo (XV).

- S.P.Q.R. (Senatus Populusque Romanus) on the quiver of the Triumph put in relation to Carbone (XII)

What is written without any ambiguity, S.P.Q.R. on the quiver of the Triumph Carbone (XII), relates to the person represented, Gaius Papirius Carbo. From the tribunal in 131 b.c.e. he had approved the lex tabellaria, much desired by the public, which extended the written, and therefore secret, ballot (tabella, tablet) to legislative meetings. It was already in force in the electoral and judiciary meetings. Of this law and its proponent, Cicero (De Leg. III, 16) said: “The third, on ordering laws or vetoing them, belongs to Carbo, a seditious and wicked citizen.”Carbo, initially a proponent of democracy, changed sides in order to attain a consular role, and passed over to the side of the aristocrats. In 120, as consul, he defended Lucius Opimius, the assassin of Gaius Gracchus, betraying both the law and his long-standing friendship with Gaius and his brother Tiberius. The following year he came to be put under indictment by Lincius Crassus, and once defeated, “it was said he took cantarella” (Cic., Ad familiares, IX, 21, meaning that he poisoned himself. Carbo was therefore considered a traitor, and the association with the Hanged Man, traditionally number XII of the Triumphs, is a perfect testimony to these facts.

It is necessary here to point out that in order to highlight the role of Lazzarelli as the author of the deck, the Brera scholars have hypothesized that this Carbone could be identified as Ludovico Carbone of Cremona, who had a connection with the Hermetist scholar. This is a debatable attribution, given that the letters S.P.Q.R. explicitly indicate a person from ancient Roman times. Chiappini also undertook enquiries in order to identify historically each character associated with the Triumphs, as he did for Carbone.

The other inscription is formed by the capital letters S and C, placed to the sides of an inverted ivy leaf. The interpretation of Hind, who assigns to the acronym S C the interpretation Senatus Consultus, is in Chiappini’s opinion unlikely. This is not so much because of its generic nature but rather because of the presence of the plant. The letters S and C wrapped around an ivy leaf in such a way appear more like a coat of arms, as if to express some family dynasty. If the mark on the card did make reference to some family, without doubt it would allude to whoever commissioned the work, who in turn would possess at least two characteristics: above all they would have acquired a certain social standing, as it was always a prerogative of the nobility to have a Tarot made for them of particular cost and value. Secondly, the geographical area in question must have been Lombardy. Based on the research done by Chiappini regarding the numbers attributed to each Triumph, he concluded that their order coincided with that of the Lombard Tarot. This evaluation coincides with what we will see in the following.

We must at this point ask whether in the second half of the 16th century there existed in Lombardy a noble family who had the possibility and above all the rank necessary to commission a work of this type. Secondly it is necessary to verify the possible relationship between the name and the acronym SC wrapped around the ivy leaf on the chariot of Deiotaro. Indeed this family does exist, and it is precisely the Busca family, who in the second half of the 1500s figured among the oldest and noblest of families of Pavia and Milan. The Busca family’s origins can be traced back to the 12th century. From one of their earliest ancestors, a certain Raimondo Busca, can be traced the origins of the lords of Cossano Belbo, a town in the province of Cuneo, had as their probable coat of arms an ivy leaf wrapped with an S and a C, the middle letters of the surname BuSCa. Even today the coat of arms of Cossano Belbo has an inverted ivy leaf, where instead of the S and C there are the letters C and B, the initials of the city.

Chiappini's investigations have also proved that in the middle of the 1500s a noble family named Busca was resident in Pavia and Milan, and their Piedmont ancestors had a coat of arms with an ivy leaf with the entwined letters S and C - the same as on the Triumphs. It therefore seems plausible that it was this family who commissioned the cards in question, also in light of the fact that one of its descendents married a member of the Sola family, which then, following the extinction of the Buscas, was the sole possessor of this Tarot deck.

From these historical findings a completely different attitude from that proposed by the Brera scholars is evident.

Regarding the identities of the personages of the Triumphs, all of them, except for the Fool, can be placed in ancient times, with reference to the indications made by Mauro Chiappini.

Triumph 0 - Mato (The Fool). Here we offer our iconological interpretation: The card has on it the Arabic numeral 0, in the form of an empty circle, perhaps suggesting the nullity of his brain. At the top the letters ‘MA’ are on one side and ‘TO’ on the other. The black crow represents the unfortunate state of the fool and also of man as irresolute and sinful, made black by his faults. Thus the Fool looks at it as if the bird was his mirror. Cesare Ripa writes about such a figure holding “nella sinistra [mano] un Corvo” (in his left [hand] a Crow) – just as the crow is on the Mato’s left, the “sinister” side: “Misfortune, as Aristotle writes, is an event contrary to the good and of every contentment. The Crow, not by being a bird of bad omen but by being celebrated as such by the poets, can serve us as a sign of misfortune; if, as oftentimes, a sad event is an omen of greater misfortune to follow, we must believe that following unhappinesses, ruins come by Divine permission, just as the ancient Omens were indications of the will of Jove. Thus we are admonished to turn from the wrong path of evil actions to the security of virtue, with which the anger of God subsides & misfortunes cease” (3). Regarding Irresolution the same author affirms: “Woman with a black cloth on her head, etc., holds two crows in her hands, which when they sing always make cras cras [in Latin: tomorrow, tomorrow], as do irresolute men who put off working diligently from one day to the next, as Martial says. “The black cloth [like the crow] shows the darkness and the confusion of their intellect ...”) (4).

One must bear in mind that the Church long considered the Fool to be the Insipiens mentioned in Psalm 52: “Dixit insipiens in corde suo: non est Deus” (The fool [insipiens] hath said in his heart: there is no God) (5). The bagpipe that the fool is playing is a pastoral instrument believed to have been used in the ancient times by sileni, wild and lascivious creatures. The instrument was therefore considered to be diabolical, like all the woodwind family. This diabolical symbolism associated with wind instruments - pipe and bagpipe, in contrast to ‘celestial’ string instruments - shows the negative character of the card. There might also have been an association to the word ‘folle’ in Latin, which meant ‘sack’ or ‘bellows’ so a ‘folle’ might be a bag of air, nothing, nonsense.

The fact that the Fool is portrayed with negative connotations from a Christian standpoint suggests a similar interpretation of the entire deck (6).

Triumph I - Panfilio. This is Marcus Baebius Tamphilus [sometimes called Panfilo in Italian], praetor of 192 b.c.e. Praetors were magistrates with executive power. He was sent to Greece with Quintus Caecilius Metellus and Tiberius Sempronius where he eased the conflicts between Thessalians and Macedonians. He also conquered the Apuani (the inhabitants of Liguria who lived in the Apuan Alps) for Rome, without shedding a single drop of blood. Thanks to this, the triumphal crown that rests on his head gains significant meaning as a prize for his victory. Moreover, he was the first to receive triumphal honors without having waged a war. First like the Magician, number one in the sequence of Triumphs.

Triumph II - Postumio. The character is Lucius Postumius Albinus, who was named a praetor and sent to Cisalpine Gaul, today’s Po Valley, to quell the inhabitants of those lands in 216 b.c.e. The Roman legions he commanded were defeated in the forest of Litana by the Boii, a Gallic tribe allied with Hannibal. His head was emptied out and decorated with gold to be used as a sacrificial chalice. According to Livy’s description, “the Boii brought the Captain’s head to one of their temples, which they revered highly. After purging its insides, they adorned it with gold, as is their custom, so that it could be a sacred vessel to be used in solemn celebrations of sacrifice, and so that it could be of use to the priest and those presiding at the Temple”. On the card his skull is portrayed in gold.

Triumph III - Lenpio. In the thousand-year history of Rome there is no one by the name of Lenpius. There is, however, a Lenius that may reasonably be the person we are looking for, to be interpreted as Lenius the Pious, transformed with a play on words into Lenpius. The man is M. Lenius Strabo. In Roman times, the nickname Strabo was attributed to those who had a visual impairment, giving us the term ‘strabismus’. He was a Roman cavalry soldier born in Brindisi, and he was the first to use aviaries in which different species of birds were kept. If one were to analyze the elements portrayed on the card, one might think that the platter resting on the ground is the one in which Claudius Aesopus placed some songbirds; the ears of wheat he holds in his hand are feed for the birds, and the gesture of covering his eye alludes to the figure’s strabismus.

Triumph IV - Mario. The card is unambiguous, even though there were many Mariuses in ancient Rome. This is Caius Marius;elected to be consul seven times, adversary of Sulla, he shackled and dragged king Jugurtha before the triumphal chariot and defeated the army of the Teutons and the Cimbri. On the card, the personage holds a shield up high as if in preparation for battle. He sits on a tree trunk; his attentive and not at all relaxed expression indicates that he is ready to go, and in his right hand he holds a shaft to which a red flag is affixed, symbol of his revenge against Sulla. The winged helm on his head is yet another symbol of his imminent victory. We are in the presence of an almost imperial figure, just as the Emperor is number IV in the traditional Triumphs.

Triumph V - Catulo. The thigh wound on this personage coincides with Orosius’s account of a man tranfixo femore aegerrime, which is to say “pierced in the thigh with the greatest pain”, referring to the consul Gaius Lutatius Catulus, who brought an end to the first Punic war in 241 b.c.e. by defeating the Carthaginians off the Aegates Islands. This victory conferred on him the honor of the Triumph. Lutatius had the praetor Quintus Valerius Faltus by his side, who expected to receive triumphal honors as well, but his claim was deemed unfounded by the Roman justice system. Thus a trutina, a scale used by the Romans to administer Justice, is shown on the card. The rod with a hat on it, a symbol for emancipation from servitude, represents this character’s liberation from the slavery that was his social and moral condition. In fact he was the first of the gens Lutatia, a plebeian family, to become a consul, despite not belonging to the Roman nobility.

Triumph VI - Sesto. The youthful appearance of this character is what leads us to believe he is Sextus Pompey, son of Pompey the Great, triumvir along with Caesar and Crassus. When Pompey lost the Battle of Pharsalus in 48 b.c.e. and fled to save himself, Cornelius and Sextus met him on the island of Mytilene and escaped to Egypt with him, where Pompey was killed before his son’s own eyes by Cleopatra’s brother, Ptolemy XIII, under orders from Caesar. This is the beginning of Sextus’s adventure against Caesar’s despotism, which led him to his premature death before the age of forty. On the card, the young man rests a shield on the ground while observing the torch in his left hand. This is the torch of life, soon to be extinguished, which the youth looks upon without regrets, his expression one of serenity and calm.

Triumph VII - Deotauro. The card leaves no room for doubt: this is Deiotarus, Chief Tetrarch of Galatia, Asia Minor, loyal ally of the Roman Republic. He was falsely accused by a nephew seeking to take his place of planning the killing of Caesar, and he was defended by Cicero in the Pro rege Dejotaro in 44 b.c.e. Cicero celebrates the Galatian king’s virtues before Caesar and the Senate: “Who is more considered than he? More cautious? And more astute? Though in this place I consider that it is not so much that Deiotarus must defend himself for his shrewdness and greatness, as for his loyalty and fearful conscience…Who does not know the probity of Deiotarus, his integrity, gravity, virtue and loyal faith?”)

Triumph VIII - Nerone. This card can be immediately traced to the Roman emperor Nero, remembered in history as a cruel and dissolute tyrant, who set fire to Rome in 64 c.e. and blamed the Christians for it, along with many other atrocities. The more authoritative historians today affirm that this is an erroneous characterization. On the card, Nero seems to be tearing apart a child before burning him. A staff is resting on his arm, the balls hanging from it reminiscent of one of those infantile Roman games called ‘tintinnabula’, the bells children would make by stringing together walnuts or hazelnuts and tying them to a wooden stick. The card’s iconography seems to suggest such an association, since these simple toys were placed in children’s tombs along with other small objects that would accompany them into the afterlife.

Triumph IX - Falco. There is only one Falco in Roman history and that is Quintus Sosius Falco, consul of 193 AD, when the cruel emperor Commodus had died and had been succeeded by the wise and prudent emperor Pertinax. Such a man could not have lasted long in a society that had already been corroded by corruption and vice. A few conspirators chose Falco to be his successor. When the terrible plot was discovered, most of the conspirators were sentenced to death, but Falco, whose guilt could not be proven and whose innocence was corroborated by many, retired to his property only to die years later of natural causes. On the card we see a kneeling man with a long gray beard, donning a crown, his right hand holding a staff, the symbol of power, while his shield and helm lie on the ground, indicating his non-violent demeanor.

Triumph X - Venturio. As there is no Venturio in Roman history, the card probably refers to one of the various Veturios that appear there, a Veturio touched by ‘ventura’ (fortune), from which, with a play on words, comes Venturio. The figure is therefore likely Titus Veturius Calvinus, twice consul, in 334 and 321 b.c.e., associated with the famous Roman defeat at the hands of the Samnites at the Caudine Forks, which occurred during his second consulship. The winged shoes he wears are not a sufficient guarantee of victory, precisely because they are a symbol of Fate, which decides human destiny. Fortune hovers in the air like the hand of the figure, indicating that the complete mastery of life is pure illusion.

Triumph XI - Tulio. The two most prestigious figures of the gens Tullia, one of the oldest of ancient Rome, are the forefather Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome during the Royal period, and Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 b.c.e.) in the Republican period. In our opinion the latter is the one that is portrayed on this card. He embodied the values of that era, a “father of the nation”, full of divine spirit, worthy of eternal memory, “a great talent who truly loved the homeland” according to Octavius who became Augustus, words written when he felt regret for having contributed, as a triumvir, to his assassination. Unlike the Hermit, who leans on a stick, he holds a torch in his hand, on top of which shines a flame, that of his works, destined to shine forever.

Triumph XII - Carbone. This is Gaius Papirius Carbo, who astribune in 131 b.c.e. had the lex tabellaria approved, extending the written, and therefore secret, ballot (tabella) to legislative meetings. Of this law and its proponent, Cicero (De Leg. III, 16) said, “The third, on adopting laws or vetoing them, is from Carbo, a rebellious and wicked citizen.” Carbo, initially on the democratic side, changed uniform and passed to the side of the aristocrats in order to become consul. In 120 b.c.e., as consul, he defended Lucius Opimius, the murderer of Gaius Gracchus, betraying (let us recall that Triumph XII was originally called ‘The Traitor’) the law and his long-standing friendship Gaius and his brother Tiberius. The following year, once defeated, he himself came to be indicted by Licinius Crassus and “it was said he took cantarella” (Cicero. Ad familiares IX,21); in other words, he poisoned himself.

Triumph XIII - Catone. Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis (95-46 b.c.e.) was an incorruptible and equitable person. Because of his moral scrupulousness, Dante places him in the Divine Comedy as a guard of Purgatory, and not among the infernal suicides, as one who “refuses life” for freedom, describing him in the Convivium as a “noble soul and the most perfect image of God on Earth.” Contrary to Caesar’s authoritarianism he preferred suicide to being arrested and participating in the end of the republican values he had always defended. With the advent of Caesar, rather than participating in the disappearance of a world for which he had lived and fought, Cato took his own life, thus achieving the highest degree of freedom in escaping the chains of dictatorial servitude. Thus the relationship with the Triumph of Death is immediate.

Triumph XIV - Bocho. Bocchus was king of Mauretania in the Jugurthine War of 108 b.c.e. Initially undecided whether to ally with the Romans or with Jugurtha, he chose his son-in-law on the promise of a part of his kingdom. Then, during the conflict, he regretted this settlement, and unsure whether to uphold the ancient alliance or take the side of the likely victors, he decided to hand over Jugurtha to the Romans. This is the recurring description of Bocchus. It appears to be the portrait of a traitor, but this is not the case. Sallustius in his work The War of Jugurtha in 42 b.c.e., describes him a wise man, immensely reasonable, sad in having to make decisions that, one way or another, would have him condemned to be judged as a despicable man.

Triumph XV - Metelo. The personage depicted is Lucius Caecilius Metellus, consul in 251 b.c.e., strategist of the defeat of Hasdrubal during the first Punic War, ensuring the supremacy of Rome in Sicily. Elected consul a second time in 247 b.c.e., four years later he was appointed Pontifex Maximus and held this high position for twenty-four years. On the card, Metellus has his head covered by a winged hat, symbol of the management of sacred things. The red conical hat with tip folded forward is one of the attributes of Mithraism, which was brought to Rome in the second/first century b.c.e., along with the sacred sceptre and the flame, here represented by the burning urn on top of the column. In fact, Mithras was one of the many masks of the light-bearing god, whether of the sacred fire of the Romans, or of the Lucifer of the later Christian tradition.

Triumph XVI - Olivo. No Olivo was handed down to us from Roman history; however we know that it was at the end of the Republic and the birth of Imperial Rome that Augustus assumed the title of divus (divine, divo in Italian) and that upon his death he ascended to the world of the gods, revered as a god (divus) of Olympus (Olimpus). From that moment, coins were made with the inscription aeternitas signifying that the memory of the emperors would never die. On this basis, it is possible to hypothesize that Olivo is the contraction of ‘OLImpo-diVO’, god of Olympus, and that the name refers to one of the emperors who, following Augustus, was worthy of a similar name. Of these, the most accredited could be Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius. Medals exist for both these men with, on the reverse side, the inscription aeternitas and a seated woman who holds with her right hand a globe with a phoenix perched on top, the bird that also appears on the card, while in her left hand a sceptre or long rod.

Triumph XVII - Ipeo. The figure most relevant to the iconology of the card is logically Hippia Helio, hence, by distortion, Ipeo, or Hippias of Elis, the eminent Greek sophist of the 5th century b.c.e. He is shown to us by historians in two ways: on the one hand as the one who sums up encyclopedic knowledge, on the other hand as one who skillfully looks at the concrete actions of humanity. The card depicts an old man in a Franciscan habit with two enormous wings on his back, praying before a tree on top of which the face of an angel appears. He is the man who does not scorn the ‘knowing how to do’ for the ‘knowing how to be’, the humble servant of earthly wisdom of the tree of life and of the enlightening wisdom of the heavens, represented here by the angelic cherub that appears at the top of the tree.

Triumph XVIII - Lentulo. There are forty-four Lentuluses, the name of one of the most important families of the Cornelian gens. A specific detail on the card, namely the transparent purple toga worn by builders, directs us towards Publius Cornelius Lentulus Spinther, who became curule aedile in 63 b.c.e., “eclipsed all who had gone before him” (Cicero, De officiis. II, XVI) and who as superintendent of theatrical and recreational activities organized a series of shows that would be remembered for their splendor, even though he ruined everything by wearing a costly and inappropriate Tyrian purple toga. Nevertheless, by all accounts, the two-time consul Lentulus is praised as a man of extraordinary wisdom, honesty and intellectual rigor.

Triumph XIX - Sabino. Conjectures put forward by various scholars suggest that the personage depicted is Theophilus Sabinus (Theophilus = loved by God) to whom the Gospel of St. Luke and the Acts of the Apostles are addressed, following the custom of classical writers of dedicating their works to famous people. The honorific with which Luke addresses him, in Greek kràtiste (most excellent, most noble), was reserved for government officials of a certain level or a person particularly worthy of esteem, as our Sabino was in life. In any case, this personage who had converted to Christianity and whom Luke wanted to lead toward a more solid and complete knowledge of the message of Christ, assumes the role of universal recipient of the message of the Gospel, sun of truth, which sun this Triumph also refers to, by the number associated with it.

Triumph XX - Nenbroto. In the Divine Comedy Dante calls him Nembrot, accusing him of having caused the confusion of languages and punishing him in Hell by making it impossible for him to communicate. He is Nimrod, who according to biblical tradition was the founder of a powerful empire in Babylonia whose nucleus was the city of Babel. Probably to him is owed the construction of the tower that instigated the whole world to rebel against the sovereignty of God by proudly erecting an instrument with which to overcome the same divine highness. On the card the personage tries to defend himself from the divine wrath represented by the tongue of fire than descends from above, however uselessly, as the punishment has already destroyed the haughtily built tower.

Triumph XXI - Nabuchodenasor. Nebuchadnezzar was a Babylonian ruler of the seventh century b.c.e., remembered above all for the conquest and destruction of Jerusalem and Solomon’s Temple. The card is probably inspired by one of the king’s two dreams interpreted by the prophet Daniel and reported in the biblical books dedicated to him, where the king, dreaming of a loss of wealth and sovereignty, gains faith, opening his eyes to the true God of the universe. In the traditional Triumphs, card XXI is the World, here represented by a starry globe above the peacefully dormant body of Nebuchadnezzar. With wrings spread across it, the Griffin. in its dual nature of lion and eagle, becomes, according to the late medieval interpretation, the figure of Christ in his human and divine nature, here put dividing the starry globe into four, in place of the four Evangelists, eternal custodians of the divine Word.

In conclusion, it is our intention to submit clothes, armor and various objects present in the cards to the attention of experts, believing that through a multidisciplinary investigation it will be possible to date the deck. We will therefore insert the results once obtained.

Notes

1 - Laura Paola Gnaccolini (ed), Il segreto dei segreti. I tarocchi Sola Busca e la cultura ermetico-alchemica tra Marche e Veneto alla fine del Quattrocento [The Secret of Secrets: the Sola Busca Tarot and the Hermetic-Alchemical culture between Marche and Veneto at the end of the 1400s], Milan, Skira, 2012, p. 18.

2 - Donald Cooper, “St. Augustine's Ecstasy before the Trinity in the Art of the Hermits, c. 1360 - c. 1440”, in Art and the Augustinian Order in Early Renaissance Italy, ed. Louise Bourdua and Anne Dunlop, Ashgate Publishing, Aldershot, UK, 2007, pp. 186-195.

3 - Cesare Ripa, Iconologia, Siena, Printed by the Successors of Matteo Florimi, 1613, pp. 371-372.

4 - Ibidm, pp. 380-381.

5 - Vulgate, Psalm 52:1; King James Version, Psalm 53:1.

6 - For a broader understanding of the Fool from the iconological point of view, see the writer's essay The Madman (Fool)

Copyright by Andrea Vitali © All rights reserved. July 2019